When I was a lad and had never messed with boats, I read Farley Mowat’s book The Boat Who Wouldn’t Float. It left an indelible impression on me. Never did I imagine that one day I would inherit a similar boat and be obliged to write a sequel.

The idea took hold while reading an article in the August, 2019 edition of Pacific Yachting describing the restoration of a classic wooden boat. Incredibly, the vessel was the same Zest we had found decades earlier, rebuilt and sailed on our adventure to the Caribbean! Matt Law, who later found her in derelict condition, generously financed her restoration and invited me for a sail to show her off. Prancing in 20-knot winds on that cold and blustery day off Sidney Spit, Zest did not disappoint. Being entrusted to the helm never felt sweeter! But Matt was curious to know the story behind Zest.

This story starts more than 40 years ago in a grocery store lineup in Calgary. I was thumbing through magazines when an article about a couple exploring the Bahamas in their 18-foot Grumman aluminum canoe caught my eye. I discussed their adventure with my partner Ursula, who said the idea of a south-sea escape sounded exciting and she would consider it for up to a year, but in a comfortable boat, and certainly not in our Klepper kayak.

We immediately started planning our adventure. I enrolled in a celestial navigation course, learned boat jargon and became proficient in capsizing and righting dinghies on Glenmore Reservoir. I was confident that my sailing skills would evolve as needed, and so would hers. Little did we suspect that our adventure would morph into more than three years, with half that time spent finding our boat and getting it ready for cruising. We also did not expect pregnancy to enter the picture and for us to move to Victoria, BC.

Finding a boat with limited funds is a challenge, especially when not knowing what constitutes a suitable boat. Nevertheless, we quit our jobs and set out in my vintage Dodge camper to find her. We travelled the full length of the West Coast of the USA, Mexico and even Central America, searching every harbour, but with no luck. We decided that Florida might be the better place to search, until a surprise phone call saved our cause; Ursula’s friends from Quebec found our boat! Her owner, the former mayor of St. Leonard, Quebec, had abandoned her and the marina wanted to recover costs and have it gone. Her name was Zest and she could be had for $1,500! We quickly drove cross-country to secure the boat of our dreams.

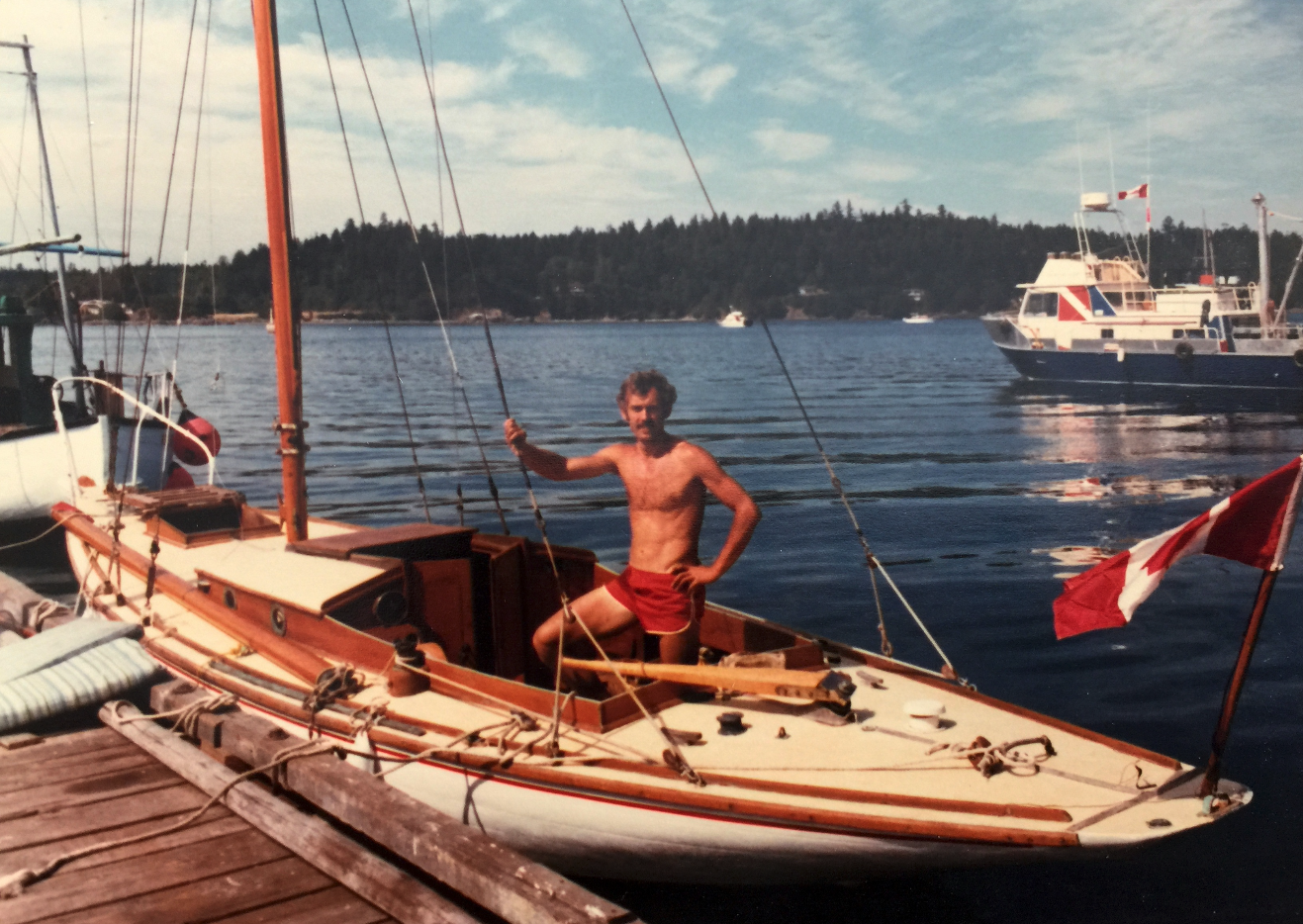

We found Zest hidden away in the dark corner of a large boat shed adjacent to the St. Lawrence River in Vaudreuil, Quebec. Despite her neglected appearance, she was beautiful to our eyes. Supported on her full-length lead keel, she exuded the confidence of a classic ocean racer whose proud days would yet return. Zest’s narrow deck, low cabin profile, graceful entry and classic overhang suggested speed even at rest.

But on closer inspection she was forsaken and badly in need of repair; her hull needed refastening, her decks needed re-planking and re-canvassing and her gutted interior needed major work to make her safe and livable. To our inexperienced eyes, she was a Cinderella awaiting rescue. Impulsively, we bought her on the spot, without a quibble or a survey! We were elated with the thought that we owned our first sailboat, and could sail to the Caribbean by a safer route, the Intracoastal Waterway. The fact that our boat still did not float, her mast and sails were missing, her engine had not been tested and we had much to learn about sailing did not deter. Together with our friends’ persuasive words and our unfailing imagination, we were locked in a strange partnership: a vintage sloop in need of restoration and a couple in need of the skills, if not resources to achieve their plan. I flinched at the thought that the result would be a boat on whose structural integrity our lives would depend.

Zest could be described as a cross between a Dragon and a Six Metre, boats still racing in our waters. Built by the famous Luke Brothers of Hamble, these Teal Class one design vessels were accomplished ocean racers designed for North Sea waters, winning the race around the Isle of Wight three times. Of the nine boats built in the 1930s, possibly three may now exist. At £1,000, they were estimated to cost more than most new English homes built at the time. Not only did they feature quality craftsmanship, but costly materials such as pitch pine, oak and mahogany. Even boom furling was a standard feature! Rich people and royalty, including Prince Phillip, sailed one. In owning a Teal, we could “hob-nob” if the occasion presented.

A letter from her architect, W. Hobbs, whose whimsical address: “Becalmed, Chichester, England,” gave us valuable insights for her restoration. He suggested we visit the Royal Cornwall Yacht Club library in England where a book by Uffa Fox, the famed British boat designer, contained a comprehensive description of her. Needing a break from Zest, we flew to England to visit Ursula’s parents, and used this opportunity to visit the prestigious seaside club in Falmouth and find this book.

We arrived in our purchased VW van late Friday evening while a boisterous party was in progress. Mistaking us as sailors just arrived by sailboat from Canada, the doorman relayed this message to the Commodore of the RCYC. He and his aid, both dressed in formal nautical attire, embraced us and offered free accommodation and access to all club facilities, including the library! Entreated to join the revelry, we were given a toast in our honour. Stoically, we deflected all questions about our comfortable journey across the Atlantic at 30,000 feet, by asking members about their harrowing experience crossing the English Channel. Miraculously, the diversion worked! We also found the book, but did not linger.

Upon returning to Canada, we began work immediately; a period that coincides with the coldest part of the Quebec winter. Our initial job was to strip the boat of all its fittings so we could refinish them in an apartment we rented nearby. Stripping a boat down to its bare essentials is not as sexy as it sounds, especially when working in a dark and musty shed with no heat. Wearing a parka, long johns, toque and gloves, the day’s routine began with shovelling away the accumulated snow that had filtered through the many cracks in the roof. I was sustained by flights of fancy: my favourite was to stand on the deck and while rocking Zest on her cradle, peer through the holes in the roof and imagine we were dodging coral heads in the sky-blue waters of the Caribbean. Not falling off the deck during seances was a miracle.

On New Year’s Day, we struggled in waist-deep snow with our boom in tow. By the time Zest was fully stripped and the engine removed, the crusty path to the shed was rapidly breaking up in the spring sunshine. Meanwhile, our basement apartment, which had turned into a workshop and marine warehouse, had turned our neighbours into wall-banging schizophrenics. Why we weren’t evicted earlier is a mystery and a god-send.

Unfortunately, Zest was designed primarily for “around the buoys racing” and not for offshore cruising. Her tall 42-foot, solid sitka spruce mast and long 16-foot boom made for a large mainsail, which could be difficult to handle in a blow. But her major liability was her large open cockpit and low freeboard. This made self-draining impractical to install. Her cramped interior and sitting headroom were equally unsuited for cruising. It was apparent that no intelligent redesign could make Zest more spacious and comfortable than our VW van!

The first of many problems surfaced within days of acquiring title to our boat. There was no record of the previous registration. We further discovered that the entire hull needed re-caulking, and garboard strakes replaced. A timely remark by the marina owner did not augur well: “If lights go out, it’s because I have just claimed bankruptcy.” The next day my diary read: “A dark and miserable day, rain flowing through every crack. Work on the engine under a tarp. Discover the engine is seized and needs rebuilding. Leave around five when the lights fail. Car won’t start. Walk home in the slush.”

Not long after, a catastrophe occurred, which made light of all our problems: the entire 150-foot shed collapsed in a windstorm with Zest and 14 other boats trapped inside. It was a delicate matter inspecting the damage as boats were bowled over and rested on each other like a game of pick-up sticks. As testimony to her construction, Zest was largely undamaged and held up the back end of the shed. The groaning and creaking of twisted timbers and flapping of metal siding made every moment in the shed a precarious and frightening experience. The radio announced continuing gusts of 110 to 130 kilometres per hour. I installed 20 jacks and supporting timbers to protect Zest from further damage, and cleared away the rubble. The good news was that we would be able to work on Zest outdoors and in the ever-increasing sunshine!

With the beginning of the boating season, life at the marina became enjoyable despite interruptions to chat and “experts” giving advice: Noting our lack of headroom, I was advised to slice the cabin top with a chainsaw and rebuild to the height needed. Returning to inspect the extra headroom achieved, this expert complimented me on my fine cut. “I merely lowered the seats,” I explained. Further advice to chop off the rotten counter and attach an outboard bracket was rejected. We preferred to remain true to preserving Zest’s lines.

The days were finally long enough to work into the evening and we experienced the warm sunshine of a Quebec summer. We had reached the point where we were putting more onto Zest than taking off. But there were temptations, as Lac des Deux Montagne, adjacent, was covered with sails, and friends invited us to join them.

As summer turned to fall, our diligence paid off: we re-canvassed the deck, restored all the fittings and varnished the mast. The new tiller was finished as was the Sampson post. The vintage gas Kermath engine was rebuilt (or so we thought). Only the electrical wiring and installation of the CB and RDF were left. But little did we realize that the launching of Zest would stretch our patience and ingenuity to their limits!

By the time we were ready to launch in September, an abnormally low lake level did not allow us to float Zest off the marina ramp. We had to rent a flatbed trailer and truck to haul our boat to the deeper waters of the Ottawa River. But first, we needed to roll Zest on her rails through the remainder of the damaged shed to an open area where we could lift her onto the flatbed for transport. Unfortunately, when it came time to push her through this shed, more demolition was required and more rails replaced. With this work completed, Zest was finally freed.

A cavalcade of honking cars accompanied the truck and flatbed carrying Zest to our new launch site. “Is this a celebration or a funeral?” Ursula asked. We were not surprised when our tow truck suffered a blown tire and our entourage was held up by rush-hour traffic. Under police escort, we eventually reached our launch site and resigned ourselves to whatever the fates next had in store.

With hearts pounding, we watched as the crane gently lowered Zest into her element. But just when she appeared to be sinking out of sight, her straps miraculously slackened. “She Floats!” I screamed repeatedly.

“So… what do you expect?” a bystander said, “It’s a boat!”

If he only knew.